….and the 8th Air Force Legacy

Today’s Beautiful Destroyers post is just a little bit different, because not only do I showcase the legendary Boeing B-17 ‘Flying Fortress’, but I also present a little game you might like to try.

The B-17 ‘Fortress’ was the mainstay (along with the B-24 ‘Liberator’) of the United States 8th Air Force, flying from bases in the UK during World War II. This aeroplane has long been one of my favourite American aircraft from WWII.

Here’s the mighty B-17G Fortress ‘Sally-B’, one of the (happily) many airworthy examples flying today. She’s dressed up as the legendary B-17F* ‘Memphis Belle’, which was the first Fortress to complete the required 25 missions to enable her crew to return home to the United States.

The doctrine which inspired the design and construction of the B-17 was that ‘The Bomber Will Always Get Through’; an inter-war concept whereby bombers would be designed that were so fast and high-flying that fighters (which when the doctrine was formulated, had similar performance to the bombers) would not be able to intercept them. However, by the time the early B-17’s were designed, they knew that the fighters would most likely be able to catch the bombers. And so the Fortress was designed, basically with guns providing all-around firepower protection; defences covering every possible approach angle so that enemy fighters would have to run the gauntlet of heavy defensive fire no matter where they attacked from – hence the nickname ‘Flying Fortress’. And so, with the benefit of this all-round armament, the Fortress was supposed to have been able to make it all the way to the target (The bomber will always get through!), without fighter escort, and defend itself (and its squadron mates, with which it flew in a defensive ‘box’ formation to maximise mutual supporting firepower) all the way to the target and back.

Of course, however, as with all such combat doctrines, the reality did not match up with the theory. Although at first, the B-17s could indeed get through to the target without serious losses, and deliver their bombs reasonably accurately, this did not last long. On the first daylight bombing mission, on 17th August, 1942, only two bombers suffered minor damage. However, the German fighter leaders of course developed tactics which they used successfully against the Fortress formations. This is what professional soldiers do well; if there is a tactic that works (in this case, massed formations of machine-gun toting bombers), you develop a counter-tactic, and so on. One of the primary such tactics was to attack the bomber formations head-on, where a) the bombers had weaker defensive weaponry (at some angles, just a single machine gun), and b) the closing speed was so high (of the order of 600mph) that accurate fire was difficult. But still the Fortresses had to go in in daylight – the whole idea was that they could actually see the target they were dropping their bombs on, unlike the RAF night raids where the bombers relied on a combination of good navigation and luck in order to hit their targets – if indeed they did hit their targets.

And so they found that the Fortress benefited from a fighter escort almost as well as did the Germans in the Battle of Britain. Both sides had learned that unescorted bombers iin daylight are vulnerable – but still the B-17 was far more capable of defending itself than were the much more lightly-armed German Heinkels and Dorniers they used in the Battle of Britain. In fact it wasn’t until early 1944 that the Fortress got a fighter escort all the way to the target; on the notorious raids on Schweinfurt and Regensburg in August 1943, the Fortresses lost nearly ten percent of their strike force, being escorted only about 25% of the way there and for the last 25% of the flight back. In October 1943, the second Schweinfurt mission resulted in such catastrophic losses (about 20%) that these missions in fact foretold the failure of the concept of deep-penetration unescorted daylight raids over Germany, in spite of the Fortress’s heavy defensive armament, and while raids continued unabated for the rest of the War, unescorted deep-penetration raids did not. Not until late 1943 were long-range escort fighters sufficiently long-legged to make it all the way to targets deep in Germany and back.

In fact, eventually, the US long-range escort fighters performed so well that some B-17 crews flew two 25-mission tours without ever seeing an enemy fighter.

The Fortress was held in high regard by its crews, because even though the bombers were regularly clobbered good and proper by both enemy fighters and flak (anti-aircraft fire), they had a reputation for being unbelievably tough.

“There were occasions where, any other airplane, took hits the way it took….wouldn’t’a brought us back…”

“God love ’em. They’d bring you home when you didn’t think you had a prayer, and, … they’d never let you down….”

“When you see what the B-17 went through, in combat, and still make it back home … it was a miracle to me”

Some Forts were indeed able to make it back home with some of the most incredible battle damage; damage that would easily have felled any other combat aircraft in the War. Some examples are given here. This Fortress, for example, was damaged in a collision with a German fighter which tracked its wingtip down across the rear fuselage and took off the left tailplane (horizontal stabiliser) too.

Or this Fort, where a Flak shell had exploded directly in front of the nose of the aircraft:

…and they incredibly managed to fly that aeroplane home! This, while extreme, is typical of the kinds of damage these aeroplanes used to absorb and still survive.

In this picture, you can see the contrails (the white vapour trails) of escorting Allied fighters above the B-17 formation:

Here’s a lovely picture of a B-17G on its bomb run. Note the spiral contrails induced by the spiral propeller wash.

And another incredibly atmospheric shot, this time a backlit picture of the propeller tips forming their own slipstream vortices:

And another beautiful picture of a B-17 formation and its contrails – beautiful but deadly. These contrails made it impossible for the defending German fighters to not see the American formations approaching.

So, the B-17 Fortress – another Beautiful Destroyer. Loved by its crews, but suffering heavy losses until the advent of 100% fighter escort.

And now for the little game, which I appreciate will only be of interest to WWII geeks 😉 I call this little exercise the ‘8th Air Force Legacy’.

During World War II, several tens of airbases were constructed during 1942-1943, in East Anglia – roughly the area east of Cambridge/Peterborough – in the United Kingdom. These bases were to be home to the tens of thousands of American servicemen whose mission it was to launch daylight air raids into Occupied Europe in order to cripple Nazi Germany’s war machine industry.

Whereas the RAF conducted its bombing campaign at night – largely a fairly indiscriminate ‘terror campaign’ waged against Germany’s civilian population (although many raids were also sent against German industrial targets in areas like the Ruhr Valley) – the US Army Air Force doctrine called for daylight precision bombing – attacks so accurate that the targets would be hit and hit hard.

The bases were placed in East Anglia so that they would be at the nearest practical ‘jumping-off point’ for raids into Europe. Raids began in August 1942 when twelve B-17s of the 97th Bombardment Group attacked the railway marshalling yards at Rouen. Within months, it became common for the skies above East Anglia to be filled with the reverberating snarl of aircraft engines as hundreds of bombers assembled their formations before commencing their long, freezing flights out over Nazi Germany and back again. Visions of the ground crews waiting anxiously for the first sound of approaching B-17s, returning from storms of flak and rivers of bullets. The culmination of the campaign against the Nazi war machine was in August 1943, where two raids were conducted against the ball-bearing plants at Schweinfurt, and the Messerschmitt factory at Regensburg, both deep in Germany, as already mentioned.

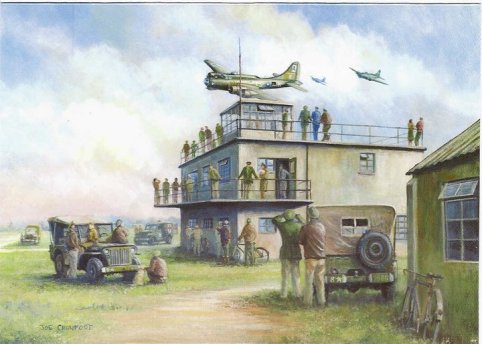

These air bases were absolute hives of activity. Thousands of personnel, hundreds of aircraft, thousands of vehicles, tons of ammunition, bombs, fuel, spare parts; busy hangars and repair shops, briefing and canteen facilities, chapels, stores, barracks – each airfield was a small town and was more-or-less self contained.

Many of these bases were closed at the end of the War, some were kept going, but now, over seventy years after the end of the War, there is in some cases little left of these once bustling places. Like navvy shanty-towns, they served their purpose, and were then left to fall into decay. Places full of memory, full of history, are now once again reverted to being farmers’ fields or other uses. Polebrook, Kimbolton, Snetterton Heath, Bassingbourn, Thorpe Abbots. Names that evoke visions of B-17s running up their engines, long grass waving behind in the prop wash, the thunder of engines as the heavily-laden B-17s rumble down the runways and lurch into the air, men playing baseball until the returning bombers could be heard, red flares on final approach to signify that the bomber had wounded aboard, wheels-up landings on one engine….

Now, here’s the game. Use Google Maps/Google Earth (satellite view) to search for the place names given below, and see if you can see the bases, or what’s left of them, nearby**. Or even just if you can see where they were. As an aid, you can type in the names of the bases into Wikipedia, and get an idea of what the shapes of the airfields were like. In Wikipedia, add RAF in front – RAF Polebrook, for example. Clue: Most of the airfields had three intersecting runways arranged in a rough overlapping triangle pattern. And take a look at what some of them are used for now – Snetterton Heath is a good example. Also, where possible, try the Google Street View on them – at Rattlesden you can even look along one of the runways that used to be used for B-17s (it’s now a gliding airfield). Would you believe that a very few of these are still active airfields in one form or another!

Here are the names you’re looking for:

Alconbury (an easy one to begin with)

Snetterton Heath

Bury St. Edmunds

Rattlesden

Knettishall

Bassingbourn

Deopham Green

Great Ashfield

Polebrook

Thorpe Abbotts

Framlingham

Grafton Underwood

Little Walden

Molesworth

Deenethorpe

Glatton

Podington (I think this is a drag-racing track!)

Chelveston (a very hard one!)

Thurleigh

Kimbolton

Ridgewell

Horham

Nuthampstead

Each of these bases was near(ish) to the village from which it took its name. Thorpe Abbotts is a bit further away, but that’s part of the fun. Look at the Google Maps from different heights and try to to spot the patterns in the ground. Polebrook is a particularly difficult one, as are Knettishall and Kimbolton. Give it a go and see how you get on. And, as always, comments are welcome 🙂

Good luck!

And finally, I found on the Internet a very moving picture of an unidentified young lady (whose face I have pixellated) walking on a disused runway at one of these old airfields***.

Look carefully above her head….

*The B-17F didn’t have the chin turret that the ‘G’ had (the twin-gun turret under the nose). The ‘Sally-B’ is a B-17G model.

**Because this article is about the B-17 ‘Fortress’, the bases included here are the ones that B-17s used for most of the war. There were also other bases, used by B-24 ‘Liberator’ heavy bombers, that were just as much a part of the 8th Air Force as the B-17s were.

If you would like to try the game with B-24 bases, here is a list of them:

Mendlesham

Shipdham

Hardwick

Hethel

Wendling

Tibenham

Bungay

Seething

Old Buckenham

Horsham St. Faith

Attlebridge

Rackheath

Sudbury

Lavenham

Halesworth

Eye

Metfield

North Pickenham

Debach

Again, good luck!

***The airfield in the ‘ghost B-17’ picture is one of those listed on this page. The challenge, of course, is to find out which one. Answers on a postcard please 😉