Well, after the wonderful night flight I did back in November, I went ahead and trained for my Night Rating to add to my Private Pilot’s Licence. I’ve already been flying on my new Rating, with my daughter Ellie – who absolutely loved the night flying – but I also wanted to go up again for some practice flying in order to consolidate my night training. Plus, I just love it!

I’ve tried to do more night flying since just after Christmas, especially wanting to take up my son David (who is also a Pilot), to let him have his first night flight, but the weather has been completely unsuitable for any kind of flying lately, let alone Night Flying, which needs a certain set of weather conditions in order to be viable*. But this week I was fortunate to have picked an evening where there was a ‘window’ of perfect flying weather, so off I went.

Here’s the aeroplane I fly, Piper PA-38 Tomahawk G-RVRL (“Romeo – Lima”), on the South Apron at Exeter International Airport, Devon, UK, which is where I fly from:

(Note: All the photographs in this post are fully zoomable; just click them to get the larger image)

I got there deliberately early so I could preflight the aeroplane in the daylight. I had her booked for a three-hour slot but that was fine – I wasn’t ‘hogging’ the aeroplane – as nobody else seems to want to do night flying at the moment. I don’t think they know what they’re missing… Anyway, ‘official night’ in the aviation world begins 30mins after local sunset, so I had plenty of time to inspect the aircraft and get her ready. For instance, in the above picture, the wing flaps have been lowered so that I can examine their condition, the hinges and control linkages, and check them for correct and symmetrical operation. You don’t just jump into an aeroplane and go flying! I have seen many Pilots – some of whom should have known better – simply check the oil and fuel and then off they go. But not me. I have a reputation for being an extremely safe Pilot and I want to keep it that way. I always perform a full (what’s called a) ‘Check Alpha’ on every aeroplane I fly. Every detail is checked, from the flaps to the fuel to the fire extinguisher to the first aid kit; my life depends on that aeroplane working properly and I leave nothing to chance, especially at night.

So, after preflighting the aeroplane, I started her up and ran the engine for a few minutes to warm it up a bit. As dusk fell and ‘official night’ drew closer, I performed all my power checks and pre-takeoff vital actions at my parking spot, so I’d be ready to go on time. This is the view from the Captain’s seat (the left hand seat) across the South Apron, just after sunset. Perfect for flying: good visibility, high cloudbase, and virtually no wind.

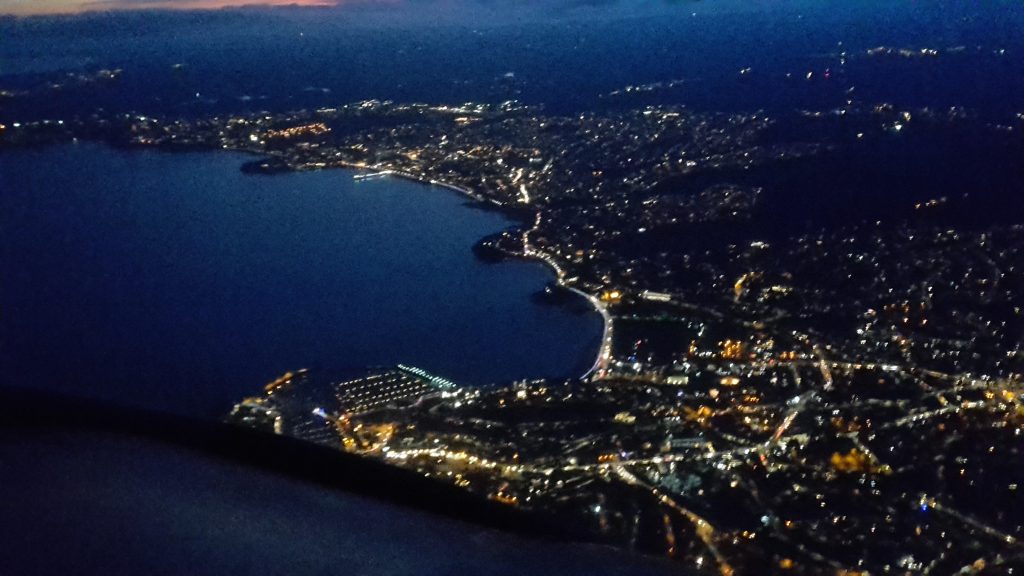

So, performing a night take-off, I climbed away from the airport and set course for Torbay, one of the most beautiful and scenic parts of the local area. All these pictures were taken with my phone’s camera, and the light was pretty dim; the phone has made the pictures make it look lighter than it actually was. But then that’s better, because then you can see what’s there…

Here’s the view from over Dawlish, looking south with Teignmouth in the foreground and Torbay in the distance. The dusk sky was absolutely beautiful, as you can see:

Looking over to the north-northeast, the lights of Exeter are visible in the growing twilight. The Exe estuary is just visible as a lighter blue patch to the right of the picture.

A few minutes later, coming up on Torquay. Torquay is the ‘capital’ town of Torbay, in the area known as the ‘English Riviera’. You can see the Marina and harbour bottom centre, with the lights of all the boats lined up at their moorings. The next town around the Bay is Paignton, and the pier is easily visible, all lit up over the water.

Directly ahead, and on the opposite side of the Bay, is the fishing port of Brixham. Paignton Pier is visible to the right, and if you know where to look (on the zoomed photo) you can just see the beginnings of the flash of the lighthouse at Start Point. As you can see, despite it being dark, the visibility is tremendous, being able to see all the way to Start Point, the southeastern tip of Devon.

A bit of a different view, now; looking out to the east and over the English Channel. Each of those small white lights shows the position of a ship or boat on the water. And of course it’s darker in that direction.

A couple of minutes after I took this photo, I inadvertently flew into cloud. At night, it’s so dark up there that you can’t always see the clouds before you’re into them. Suddenly, you can’t see the ground anymore, and you are surrounded by a silver-grey flickering, billowing mist, illuminated by the flashing wingtip strobe lights on the aeroplane. But this is easily remedied in that you go straight on to instruments (which, at night, you’re doing for much of the time anyway) and do a gentle, level 180-degree turn out of the cloud. After only 90 degrees of turn, I was clear of the cloud anyway – it must have been only a small one – but in order to prevent any further cloud incursion, I descended 300ft or so in order to be sure I was completely clear of the cloudbase. This illustrates the sort of quick decision-making, forward thinking and real-time tactical planning that is essential in all flying, but particularly at night.

Over the middle of Paignton, now, this slightly blurry photo is of the main crossroads on Torbay Ring Road, known as ‘Tweenaway Cross’. The famous tourist attraction, Paignton Zoo, is just below the orange area at the bottom of the picture (the orange area is a supermarket car park (Morrisons)). Note how the little remaining light from the sky reflects off the aeroplane’s wing…

The night was completely dark not long after that shot. Although the moon was up, it was only just over half-full and didn’t really illuminate all that much on the ground, if anything.

Thoroughly enjoying myself, I was struck once again by the wonder of flight, and night flying in particular. This was the sort of flight where I simply didn’t want to come down!

It’s almost surreal, and, if you think about it, almost counterintuitive. Here we are, tanking along at what amounts to nearly a hundred miles an hour, over half a mile above the ground, and I can’t really see where I’m going, and yet it all works. Incredible! I suppose there’s nothing to actually run into up here; even other aeroplanes are easy to spot because, like mine, they have lights on them and also I have a radar service from Exeter Radar – kind of like an extra pair of eyes, if you like. But tonight, apart from a few airliners being directed in to Exeter, I’m the only aeroplane up here. It’s all very quiet and quite beautiful.

Heading back up towards Exeter from Torbay, I flew over Newton Abbot, and took this picture of the Penn Inn flyover, part of the South Devon Expressway. This is a long-awaited road that has transformed the transport links in this area, and it has been open for just over two years. Prior to the opening of the Expressway (also known as the Kingskerswell bypass), road users from Torbay and all the areas beyond had to queue through the town of Kingskerswell, adding at least half an hour to their journeys. This road has opened up the area like nothing else. And here’s what it looks like at night:

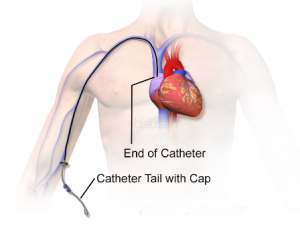

Finally, here’s a photo of the final approach into Exeter’s Runway 26, with all the lights and whatnot. This photo was taken back in December by my daughter; because I was by myself on my latest flight, I couldn’t have taken a photo myself at this point, having my hands full with the landing and all. Features to note are the approach lights (the yellow lights laid out like a Christmas tree) which help the Pilot line up properly with the runway, the green threshold lights, showing the start of the runway, the main flarepath lights which show the runway itself, and the short row of four lights to the left of the runway. These are what’s known as ‘PAPI lights’ (Precision Approach Path Indicator) and they show you if you are on the correct glideslope. Two white and two red means you are on slope, like in the picture. If you are too high, more of the lights turn white; if you are too low, they turn red. So four reds is way too low, four whites is way too high. Part of the night rating training is to learn how to land without the approach lights, and/or without the PAPIs, to help the trainee learn how to land at night in the event of failure of those particular lights, and also to learn how to land at aerodromes that do not have those kinds of lights (not all do). However, if the main runway lights are unserviceable, you’re talking diverting to another aerodrome because those lights really are essential for a safe landing. The others are just trim; they make things easier but they are not essential.

So, there we have it. An absolutely magical flight for me, some lovely photos (although flying at night does make it harder for the Pilot to do photos; better if he has a camera-armed passenger!) and a safe landing at the end. In fact, it was one of the best landings I have ever done, and in the dark as well! I think it’s going to take me at least a week to lose these euphoric feelings that happen when I fly, and especially at night. Walking back across the airfield from the aeroplane to the flying club, I was actually laughing out loud with the sheer joy of it all. Thankfully it is a huge, dark airfield, and there was no-one nearby to hear 😉

Once the nights get lighter, and night flying falls off the end of the airport’s opening times, I will be daylight flying again right up until the autumn. I will really miss night flying at that time; I really love it and to be honest there’s nothing quite like it. So I am going to get in as much night flying as I can before the cutoff around Easter!

Love it!

Header picture shows the Teign estuary all the way from Teignmouth to Newton Abbot, and the glorious sky beyond.

*Ok, I will explain: in night flying, I still have to fly under what’s called ‘visual flight rules’ or VFR. This means I still can’t fly in cloud (although sometimes I might inadvertently enter a cloud – like in this story – because you just can’t see them at night). For that reason, not only does the weather at Exeter have to be good enough for VFR flying, but also the weather forecasts at my planned diversion airfields, and the en-route weather to those airfields. Why is this more exacting at night than it is in daylight? Well, it’s because, in daylight, if you have a problem at your home aerodrome (say someone’s pranged an airliner and blocked the runway, or there’s a terrorist incident or something that closes the airport), in a pinch you can just land in a field if necessary; it’s called a precautionary landing. At night, you can’t even see the fields. As you can see from the photos in this piece, even when it’s still twilight, everything that isn’t a town or road is simply black and you can’t see what’s actually there. And so, in case such an aerodrome closure event occurs, you have to plan to be able to fly to another major airport that has runway lighting; in my case that would be Bristol, Bournemouth, Cardiff or Newquay-Cornwall. Or, if Dunkeswell are doing night flying, I could go there (it’s only ten miles away). So you see the planning and weather briefing has to be much more detailed for night flying. Of course, that’s all part of the training…

Talking of precautionary landings, one wag once told me that if you have to do one at night, you switch on your landing light (it’s like a small car headlight) and take a look. If you don’t like what you see, you switch it back off again… 😉