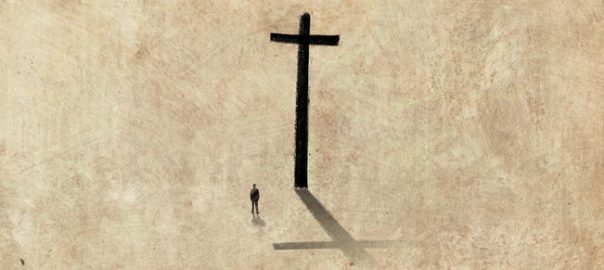

Whatever you need the Cross of Christ to be, for you, it will meet that need. It’s often been said that at the Cross, God meets all the deepest needs of mankind. Reconciliation with God? Check. Healing? Check. Forgiveness? Check. Putting to death of the ‘old nature’? Check. A sacrifice? Check. Demonstration of God’s love for us? Check. I myself no longer see the Cross as being the place where Jesus was sacrificed as a Lamb to appease a wrathful god. But if you, personally, need the Cross to be the place of sacrifice, then God is big enough, and the work of Christ at Calvary is huge enough, to meet that need. And that’s fine. Others will likely have different needs, and that’s fine too.

For myself, I no longer see the Cross through the lens of ‘penal substitutionary atonement’ (PSA), where Jesus ‘took my place’. I no longer consider PSA to be a viable Biblical concept, although I do understand why people believe that idea. I used to believe it myself, once upon a time. I’m generally not very good at describing what the Cross means to me, because it’s more of an internalised thing for me, although I have expressed some of my ideas in previous blog posts. I know what it means to me, and I know that I am continually learning more about just what Jesus did there. At the bare minimum, if we fix ourselves to just one particular interpretation, or ‘meaning’, of the Cross, we will miss out on learning so much more about what Jesus did there.

And so, for your upbuilding, here is a beautiful piece by the brilliant Jacob M. Wright, where he presents a superbly logical and totally Biblical idea on a particular aspect of the Cross. As usual, Jacob expressess his ideas with clarity and conviction:

Here is a couple lines from a beautiful and scathing critique of Christianity by Sam Harris. Part of his critique is of the superstitiously violent nature of religion throughout history and its nearly universal practice of sacrificing humans in a myriad of different horrific ways to “appease the gods” or satisfy strange superstitions. I fully agree with him in this particular critique and I believe a very different interpretation of the crucifixion which I will briefly go over afterwards.

“Upon seeing Jesus for the first time, John the Baptist is rumored to have said, ‘Behold the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world’ (John 1:29). For most Christians, this bizarre opinion still stands, and it remains the core of their faith. Christianity is more or less synonymous with the proposition that the crucifixion of Jesus represents a final, sufficient offering of blood to a God who absolutely requires it (Hebrews 9:22-28). Christianity amounts to the claim that we must love and be loved by a God who approves of the scapegoating, torture, and murder of one man—his son, incidentally—in compensation for the misbehavior and thought-crimes of all others.

“Let the good news go forth: we live in a cosmos, the vastness of which we can scarcely even indicate in our thoughts, on a planet teeming with creatures we have only begun to understand, but the whole project was actually brought to a glorious fulfillment over twenty centuries ago, after one species of primate (our own) climbed down out of the trees, invented agriculture and iron tools, glimpsed (as through a glass, darkly) the possibility of keeping its excrement out of its food, and then singled out one among its number to be viciously flogged and nailed to a cross.”

I appreciate Harris’ brilliant words here in so much as he is exposing the wrong way of seeing Christianity. This is why we need to continue to overturn Calvin’s model of the atonement and show that with Christ we do not have what every other religion has in terms of slaughtering a creature to appease its god with blood, but rather we have a subversion of sacrifice and an overturning of normal sacrificial thinking.

I would start by pointing out that if the bloody torture and crucifixion of Jesus was demanded by God to appease his wrath, then why are Jesus torturers and killers considered evil in carrying out this act, if they were merely fulfilling a necessary barbaric human sacrifice ritual unto God and with every drop of blood appeasing him?

Here is the normal sacrificial routine: those bringing the sacrifice are considered righteous and pleasing to God by bringing an offering to slaughter unto God. Now contrast with Christ’s Passion: The ones carrying out the act are evil, not pleasing to God. And the one bringing the offering (“I lay my life down of my own accord”) is God himself who is offering himself to humanity. This is the opposite of a divine wrath-appeasing human sacrifice model. This is completely turned on its head.

If they were carrying out an act that in itself was good and pleasing to the Lord, namely torturing and killing Jesus as a human sacrifice to satisfy God’s wrath, then why did God go about it the way he did? Why didn’t Jesus just explain to his disciples to tie him down to an altar, slaughter him, and burn his flesh as a pleasing sacrificial aroma to God? Instead we have the opposite playing out, that it was an evil act and that it was God offering himself up to the hands of sinful men, rather than humans offering a sacrifice to God. The Passion is a subversion of the sacrificial system.

Furthermore, we have Paul explaining that God offering himself to be killed by the hands of sinful men was an exposure and defeat of the principalities and powers and it was God making peace with humanity, in contrast to a sacrifice where humans try to appease and make peace with God. Usually it was man trying to reconcile God to himself through their offering to God but here we have God reconciling the world to himself through his offering of himself.

To go further, the normal pagan sacrificial ritual was to satiate the bloodlust of the gods with the flesh and blood of the sacrifice. Whereas in the Passion narrative, God’s flesh and blood is offered to us, and we are the ones who eat and drink the flesh and blood of God.

The Passion shows us to be the ones with the bloodlust, not God. God subverts this nearly universal practice of sacrifice to expose something at the heart of humanity and to transform human thinking concerning who God is and who we are. We are thus transformed by coming again and again to remember this act of self-giving, unconditionally forgiving love, remembering the One who does not demand blood but lays down his own life to make peace. We partake in this act, we receive unconditional forgiveness, and we are called to be transformed into peacemakers ourselves.

This is how Jesus’ sacrifice was pleasing to God. Not because God demanded it or was satisfied with a blood offering, but because as the writer of Philippians says, Jesus “emptied himself”, demonstrating the humility of a servant, laying his life down in non-violent forgiveness, dying a victims death at the hands of violent humanity. This was a perfect act of love, and thus God exalts Christ to supreme authority, that at his name, everyone will surrender and every tongue confess that this love is the supreme authority. Within this act of divine love is the reconciliation of all things.

God did this at the risk of being thought of as normal sacrificial thinking, that is, an animal or human being offered to God to satiate his bloodlust and appease his anger. Yet even when people see it that way, it still communicates the final doing away with sacrifice with an act of self-giving and peacemaking which begins to deconstruct these sacrificial paradigms in social thinking. Even when one cannot see the powerful subversion of sacrifice at work in Christ’s act, and they see it through the lens of normal sacrificial thinking, it still begins the necessary deconstruction of sacrificial thinking and begins to end sacrifice once and for all in civilization, and begins to point to a God of self-sacrifice, forgiveness, self-giving love, and reconciliation, which begins working itself through human thinking and overturning our violence and enmity with Christ’s act of peacemaking and reconciliation.

– Jacob M. Wright, used with his kind permission